Top Quality Audio Is Key to Finding Good Records

Top Quality Audio Is Key to Finding Good Records

There is a truism (a statement that is obviously true and says nothing new or interesting) that frequently pops up in the comments section commonly found on audiophile forums.

Working similarly to Godwin’s law, the longer an audiophile thread goes on, the more likely it is to be said. A quick recap of Godwin’s law:

“Godwin’s law, short for Godwin’s law (or rule) of Nazi analogies, is an Internet adage asserting: “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches 1.”

The truism I’m talking about is commonly phrased, “It’s the music, stupid,” an echo of James Carville’s “It’s the economy, stupid,” from Bill Clinton’s campaign. (I prefer not to use the word “stupid” when discussing my fellow audiophiles’ comments, but the play on words does not work without it, so there it is.)

Who would be foolish enough to take up the other side of this “argument,” if we can call it that?

Allow me to have a go at it.

So, if I understand correctly, it’s all about the music, right? Not the sound?

What about other kinds of art? What is it about there?

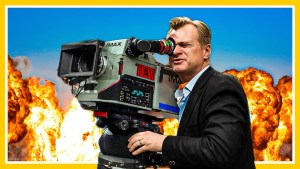

Christopher Nolan shoots on IMAX film, which I believe in its current iteration is either 65 or 70mm.

If his movies are about a story and its characters, why not shoot them on 35mm? Or 16mm. Or Super 8? Or, gasp, digital?

Same story, same characters. But it sure wouldn’t be the same experience.

And nobody has trouble understanding that. Here’s Nolan on 70 mm.

“[The] sharpness and the clarity and the depth of the image is unparalleled. The headline, for me, is by shooting on IMAX 70 mm film, you’re really letting the screen disappear. You’re getting a feeling of 3-D without the glasses. You’ve got a huge screen and you’re filling the peripheral vision of the audience. You are immersing them in the world of the film.“

But music is different for some reason? To paraphrase Joe Pesci, different how?

Music is nothing but sound, so without good sound, what do you really have?

When it comes to pop and jazz tunes, the broad outlines of a song can be understood even through very bad sound. I grew up listening to The Beatles on my transistor radio. Their music sounded amazing to me.

But is that true of symphonic music? Can you possibly understand The Rite of Spring by playing it through a computer speaker or iphone?

In no other aspect of life outside of music does anyone want to put up with the lowest possible quality.

Bad food, bad clothes, bad cars, bad TVs — none of these are acceptable, at least not to anyone I know.

But bad sounding music? MP3 sound? CD sound? Heavy Vinyl sound?

Not a problem! 99.999% of the music listeners of the world accept that level of quality every day. They don’t care about the quality of the sound and they think that those who do are fools who are conmpletely missing the point. We’ve all run into these people. Who can say that our way of listening is any better than their way?

It Can’t Be

The one place where it cannot just be about the music is on an audiophile thread. Audiophiles are lovers of sound, not lovers of music. (Lovers of music are, I’ve just learned, “melophiles.”)

The one place such a tiresome truism as “it’s about the music” has no business is where audiophiles are talking about the sound of recordings. The music has to be secondary to the quality of the sound. The sound of whatever is being described — a heavy vinyl pressing, an original LP, a CD, a cassette — is what is of interest to those of us who go to audiophile websites and forums.

The “value” of these places — a word we would never use in this context without scare quotes, as we do not find much value to be had there — is to be pointed in the direction of music, any music, as long as it has good sound.

What pressing sounds better than what other pressing? What mastering engineer did a better job on an album than some other mastering engineer?

Whether you like the music on Album X is of much less concern to me than what you say about its sound.

If, in your audiophile opinion, you prefer the sound of one pressing over another, that is something that might have some value to me. I’m always looking for higher quality sound.

I don’t care what you think of the music; that’s your business and none of mine. I’m perfectly capable of making my own judgments about the music I listen to, thank you very much. All I want to know is which version of the album conveys the music we are discussing better than others.

Except in some rare cases, the music is the same for all the pressings of it. How on earth can it be about the music if the music is always the same?

You can choose to watch Oppenheimer on your phone. You have the right to make that choice. If you do make that choice, can you talk about the experience of seeing the movie the same way that someone who saw it in an Imax theater is able to talk about the experience? Would you be in a position to comment on how powerful the image was, or how powerful the sound was? How either of them, or both, made you feel?

You can play records back on bookshelf speakers shoved up against a wall in a back bedroom, but should you really be talking about the experience of hearing the music in such compromised circumstances?

Sure, you heard the music, but some rather large percentage of the sound was not conveyed to you, so why would you want to discuss the pros and cons of sound that you barely heard?

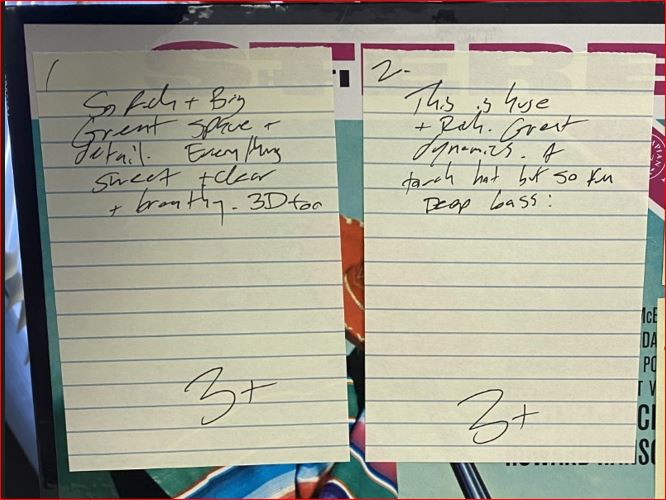

As you will see in the commentary reproduced below, I want to hear recorded music sound like live music.

I don’t have much use for bad sounding music. If the music doesn’t sound good, then I probably don’t want to listen to it. (If I go to a live venue and the sound is bad, more often than not I just leave.)

Finding good music with good sound on vinyl is not a problem, because the record world is overflowing with thousands and thousands of great sounding pressings, many of which I have yet to discover.

I can easily find great sound for the music I already love, because a very large part of what makes my favorite music so emotionally satisfying to listen to is the fact that it is exceptionally well recorded. Emotionally satisfying and exceptionally well recorded are not independent of each other. They work together and reinforce each other.

If you find yourself on a forum, and you feel the need to remind the other posters there that “it’s about the music,” check to see if it’s a forum dedicated to audiophile sound, and if it is, consider saving your breath. Surely you have something more interesting to say.

The section below is reproduced from this post and talks about what I was aiming for in building my stereo system and room.

In Geoff Edgers’ Washington Post article about audiophiles, somebody asks “why would you want to go into a room and just play a record by yourself?”

I would answer the question with a question of my own: why would you go to a museum and just look at a painting by yourself?

You don’t need anybody around you to help you understand a painting.

You just look at the painting and that’s the experience of looking at a painting.

When I listen to a record, I want the experience of listening to the record. I don’t need anybody else around. I don’t need anybody talking to me. I just want to hear that record, and as Nathan said, I want it to take me from the beginning to the end. And at the end I should feel like I still want more.

For me, that’s what a good record and a good stereo is all about. That’s the reason some of us describe ourselves as audiophiles.

The shortest definition of an audiophile is a “lover of sound.” I love good sound and I’ve spent more than forty years building a stereo system that has what I think is very good sound. (What others think of it has never been of much concern, nor should it be.)

It’s in a dark room with no windows because music sounds better in a dark room with no windows. Keet the door closed, too.

There is one chair and it is located in the sweet spot in the room. (Yes, there can only be one sweet spot.)

I go in there to put myself in the living presence of the musicians who performed on whatever records I choose to play.

Music is loud and so I play the stereo at levels as close to live music as I can manage.

The system creates a soundfield that stretches from wall to wall and floor to ceiling. With the speakers pulled so far out into the room, they have often been known to disappear, leaving only three-dimensional imaging of great depth and precision (especially in the case of orchestral music).

By listening this way, I am able to completely immerse myself in the music I play, with no distractions of any kind.

This way of listening is more intense and powerful and transportive than any other I have known (outside of the live event of course).

That’s what I am trying to achieve with my system and the best records I can find to play on it: an experience that is so intense and powerful that I find myself completely transported out of the real world I exist in, and into the imaginary world created by the producers, engineers and musicians responsible for making the record.

If you want this kind of experience, you need more than good music. You need a good recording of that music, and, if you’re an analog sort of person with high standards, you need an exceptionally good pressing of that recording.

At the highest levels of sound quality, for us audiophiles it can’t just be about the music. You really do need all three.

Depending on your tastes and standards, good music can easily be found most everywhere. Good music with good sound, at least on vinyl, is much more rare, and good sounding music reproduced well is, in my experience, very rare indeed.

Some people are upset and put off by what they consider to be our “extreme” approach to records and audio. It bothers them that we constantly say that doing records and audio well is harder than it looks. To them it seems so easy.

Naturally, we believe there is ample evidence to support our views on the subject.

And, to paraphrase Jesus, the upset will always be with us.

Robert Brook has given this subject some thought as well: My system, what it’s built for, and why

(more…)

Robert Brook has a blog which he calls

Robert Brook has a blog which he calls

Top Quality Audio Is Key to Finding Good Records

Top Quality Audio Is Key to Finding Good Records