More Direct to Disc Recordings

More Classical and Orchestral Recordings

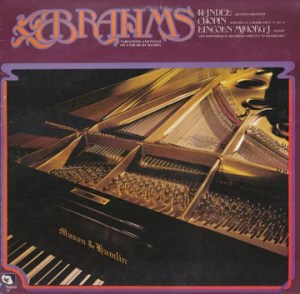

- Lincoln Mayorga‘s wonderful performance of these classical works for solo piano returns to the site for only the second time in years, here with STUNNING Shootout Winning Triple Plus (A+++) sound or close to it throughout this original Sheffield Direct to Disc import pressing

- As we discovered many years ago, all pressings of this recording are out of polarity – you must reverse the polarity of your system to hear this record properly

- Out of polarity, it sounds shockingly small, practically mono – with the polarity corrected, it is as big and real as if you were listening to the recital live from the front row

- Both of these sides are amazingly rich, spacious, and transparent, with an exceptionally clear, solid and present piano and virtually no trace of smear

- This copy fulfills the promise of the audiophile-oriented recording in a way that few – shockingly few, to be honest – pressings of its kind ever have

This Sheffield Direct-to-Disc LP is one of the best records ever put out by Sheffield.

Lincoln Mayorga is an accomplished classical pianist: this is arguably his best work. (I had a chance to see him perform at a recital of Chopin’s works early in 2010 and he played superbly — for close to two hours without the aid of sheet music I might add.)

This vintage pressing has the kind of Tubey Magical Midrange that modern records can barely BEGIN to reproduce. Folks, that sound is gone and it sure isn’t showing signs of coming back. If you love hearing INTO a recording, actually being able to “see” the performers, and feeling as if you are sitting in the studio with the band, this is the record for you. It’s what vintage all analog recordings are known for — this sound.

If you exclusively play modern repressings of vintage recordings, I can say without fear of contradiction that you have never heard this kind of sound on vinyl. Old records have it — not often, and certainly not always — but maybe one out of a hundred new records do, and those are some pretty long odds.

What The Best Sides Of Variations And Fugue On A Theme By Handel & More Have To Offer Is Not Hard To Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1976

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

Copies with rich lower mids and nice extension up top did the best in our shootout, assuming they weren’t veiled or smeary of course. So many things can go wrong on a record! We know, we’ve heard them all.

Top end extension is critical to the sound of the best copies. Lots of old records (and new ones) have no real top end; consequently, the studio or stage will be missing much of its natural air and space, and instruments will lack their full complement of harmonic information.

Tube smear is common to most vintage pressings. The copies that tend to do the best in a shootout will have the least (or none), yet are full-bodied, tubey and rich.

What We’re Listening For On Variations And Fugue On A Theme By Handel & More

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

Side One

Air With Variations: Handel

Variations And Fugue On A Theme By Handel: Brahms

Aria, Variations 1-13

Side Two

Variations And Fugue On A Theme By Handel: Brahms

Variations 14-25, Fugue

Mazurka In A Minor, Opus 17, No 4: Chopin

Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel

The Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24, is a work for solo piano written by Johannes Brahms in 1861. It consists of a set of twenty-five variations and a concluding fugue, all based on a theme from George Frideric Handel’s Harpsichord Suite No. 1 in B♭ major, HWV 434. They are known as his Handel Variations.

The music writer Donald Tovey has ranked it among “the half-dozen greatest sets of variations ever written.” Biographer Jan Swafford describes the Handel Variations as “perhaps the finest set of piano variations since Beethoven,” adding, “Besides a masterful unfolding of ideas concluding with an exuberant fugue with a finish designed to bring down the house, the work is quintessentially Brahms in other ways: the filler of traditional forms with fresh energy and imagination; the historical eclectic able to start off with a gallant little tune of Handel’s, Baroque ornaments and all, and integrate it seamlessly into his own voice, in a work of massive scope and dazzling variety.”

Structure

In Music, Imagination, and Culture Nicholas Cook gives the following concise description:

The Handel Variations consist of a theme and twenty-five variations, each of equal length, plus a much longer fugue at the end which provides the climax of the movement in terms of duration, dynamics, and contrapuntal complexity. The individual variations are grouped in such a way as to create a series of waves, both in terms of tempo and dynamics, leading to the final fugue, and superimposed on this overall organization are a number of subordinate patterns. Variations in tonic major and minor more or less alternate with each other; only once is there a variation in another key (the twenty-first, which is in the relative minor). Legato variations are usually succeeded by staccato ones; variations whose texture is fragmentary are in general followed by more homophonic ones. … the organization of the variation set is not so much concentric—with each variation deriving coherence from its relationship to the theme—as edge-related, with each variation being lent significance by its relationship with what comes before and after it, or by the group of variations within which it is located. In other words, what gives unity to the variation set … is not the theme as such, but rather a network of ‘family resemblances’, to use Wittgenstein’s term, between the different variations.

There are various opinions about the organization of the Handel Variations. Hans Meyer, for example, sees the divisions as nos. 1–8 (‘strict’), 9–12 (‘free’), 13 (‘synthesis’), 14–17 (‘strict’) and 18–25 (‘free’), culminating in the fugue.[15] William Horne emphasizes paired variations: nos. 3 and 4, 5 and 6, 7 and 8, 11 and 12, 13 and 14, 23 and 24. This helps him to group the set as 1–8, 9–18, 19–25, with each group ending with a fermata and preceded by one or more variation pairs. John Rink, focusing on Brahms’s dynamic markings, writes,

Brahms takes pains to control the intensity level throughout the twenty-five variations, maintaining a state of flux in the first half, and then keeping the temperature perceptibly low after the peak in Variations 13–15 until the massive ‘crescendo’ towards the fugue begins in Variation 23. We thus find a sensitivity to motion and momentum that complements—and possibly transcends in importance to the listener—the elegance of structure about which so many authors have (legitimately) enthused.

Unity is maintained, at least in part, by using Handel’s key signature of B♭ major throughout most of the set, varied by only a few exceptions in the tonic minor, and by repeating Handel’s four-bar/two-part structure, including the repeats, in most of the work.

-Wikipedia