More of the music of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

More Orchestral Spectaculars

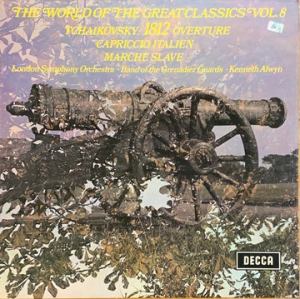

- Outstanding sound from start to finish – this Decca recording of the 1812 from 1958 is the only one we know of that can show you the power of Live Music for this important work

- This UK pressing is BIG, lively, clear, open and resolving of musical information like no copy of the 1812 you’ve heard

- The two coupling pieces, Marche Slave and the Capriccio Italien, also have rich, powerful, weighty brass and lower strings

- The most exciting and beautifully played 1812 we know of – we encourage you to compare this to the best orchestral recording in your collection and let the chips fall where they may

- When you hear how good this record sounds, you may have a hard time believing that it’s a budget reissue from 1970, but that’s precisely what it is. Even more extraordinary, the right copies are the ones that win shootouts

- There are about 150 orchestral recordings we’ve awarded the honor of offering the Best Performances with the Highest Quality Sound, and this recording certainly deserve a place on that list.

There is some noticeable low frequency rumble under the quietest passages of the music for those of you with the big woofers to hear it!

The lower strings are rich and surrounded by lovely hall space. This is not a sound one hears on record often enough and it is glorious when a pressing as good as this one can help make that sound clear to you.

The string sections from top to bottom are shockingly rich and sweet — this pressing is yet another wonderful example of what the much-lauded Decca recording engineers (Kenneth Wilkinson in this case) were able to capture on analog tape all those years ago.

The 1958 master has been transferred brilliantly using “modern” cutting equipment (from 1970, not the low-rez junk they’re forced to make do with these days), giving you, the listener, sound that only the best of both worlds can offer.

More of the music of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

More of the music of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) A few days went by while we were cleaning and listening to the hopefuls. We then proceeded to track down more of the pressings we had liked in our preliminary round of listening. At the end we had a good-sized pile of LPs that we thought shootout-worthy, pressings that included various RCA, Decca and London LPs.

A few days went by while we were cleaning and listening to the hopefuls. We then proceeded to track down more of the pressings we had liked in our preliminary round of listening. At the end we had a good-sized pile of LPs that we thought shootout-worthy, pressings that included various RCA, Decca and London LPs.