More of the music of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Hot Stamper Classical Imports on Decca & London

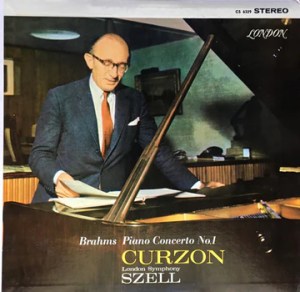

- Incredible sound throughout this early London pressing of Curzon and the LSO’s dynamic performance, with a STUNNING Shootout Winning Triple Plus (A+++) side two mated to a solid Double Plus (A++) side one

- It’s also fairly quiet at Mint Minus Minus, a grade that even our most well-cared-for vintage classical titles have trouble playing at

- Both sides boast full brass and an especially clear, solid, present piano, one with practically no trace of smear — the right combination of richness and clarity is what allows the best pressings of this album to sound like live music

- With huge amounts of hall space, weight and energy, this is a Demo Disc by any standard

- Some old record collectors (like me) say classical recording quality ain’t what it used to be – here’s all the proof anyone with two working ears and top quality audiophile equipment would need to make that case

- Speakers Corner did a creditable job remastering the record back in the early days of Heavy Vinyl, but one thing you can be sure of: theirs won’t hold a candle to the Hot Stamper pressings we are offering

This vintage London pressing has the kind of Tubey Magical Midrange that modern records can barely BEGIN to reproduce. Folks, that sound is gone and it sure isn’t showing signs of coming back. If you love hearing INTO a recording, actually being able to “see” the performers, and feeling as if you are sitting in the studio with the band, this is the record for you. It’s what vintage all analog recordings are known for — this sound.

If you exclusively play modern repressings of vintage recordings, I can say without fear of contradiction that you have never heard this kind of sound on vinyl. Old records have it — not often, and certainly not always — but maybe one out of a hundred new records do, and those are some pretty long odds.

What The Best Sides Of Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 Have To Offer Is Not Hard To Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1962

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

Copies with rich lower mids and nice extension up top did the best in our shootout, assuming they weren’t veiled or smeary of course. So many things can go wrong on a record! We know, we’ve heard them all.

Top end extension is critical to the sound of the best copies. Lots of old records (and new ones) have no real top end; consequently, the studio or stage will be missing much of its natural air and space, and instruments will lack their full complement of harmonic information.

Tube smear is common to most vintage pressings. The copies that tend to do the best in a shootout will have the least (or none), yet are full-bodied, tubey and rich.

Size and Space

One of the qualities that we don’t talk about on the site nearly enough is the SIZE of the record’s presentation. Some copies of the album just sound small — they don’t extend all the way to the outside edges of the speakers, and they don’t seem to take up all the space from the floor to the ceiling. In addition, the sound can often be recessed, with a lack of presence and immediacy in the center.

Other copies — my notes for these copies often read “BIG and BOLD” — create a huge soundfield, with the music positively jumping out of the speakers. They’re not brighter, they’re not more aggressive, they’re not hyped-up in any way, they’re just bigger and clearer.

And most of the time those very special pressings are just plain more involving. When you hear a copy that does all that — a copy like this one — it’s an entirely different listening experience.

What We’re Listening For On Piano Concerto No. 1

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Powerful bass — which ties in with good transient information, also the issue of frequency extension further down.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

Production and Enginneering

John Culshaw produced and Kenneth Wilkinson engineered this recording for Decca in 1962 in the wonderful Kingsway Hall that the LSO perform in. If you know much about Golden Age classical recordings, you recognize these names as giants who strode the earth many years ago.

60+ years later we continue to be astonished by their achievements.

TRACK LISTING

Side One

Piano Concerto No. 1 In D Minor Op. 15

Maestoso

Side Two

Piano Concerto No. 1 In D Minor Op. 15

Adagio

Rondo – Allegro Non Troppo

Classical Candor.com Review

English pianist Sir Clifford Curzon made the recording with George Szell and the London Symphony Orchestra over half a century ago, and no one has yet to surpass it.

Curzon (1907-1982) made a ton of recordings in his lifetime, yet he left us with only a relative few. That’s largely because he was a notoriously fussy perfectionist when it came to what he wanted the public to hear and refused to allow record companies (mainly Decca, with whom he recorded almost exclusively) to release any number of his recordings he didn’t think were up to his standards. He just didn’t feel satisfied with them. Fortunately, the Brahms was among the few things to get through and remain in the catalogue.

As I’m sure you’re aware, Brahms wrote his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1858 while he was still a fairly young man. I continue to see the work as all craggy and monumental in scope, and Curzon’s potent interpretation (one of the first I remember hearing) is a chief reason for how I think of the Brahms today. The work also abounds in energy and vitality, perhaps the energy of youth, and here I think of Curzon as well, even if he was in his mid fifties when he recorded it.

…after a lengthy and properly regal orchestral introduction from Szell and the LSO to set the tone, Curzon enters with elegant power. While the First Piano Concerto may be a youthful work, Curzon does not overemphasize the fact with any excessive playfulness. Indeed, his is a mature, patrician account, frank and straightforward, and all the better for it. Yet it is also a kind of cozy account, especially in terms of the interplay between soloist and orchestra. Everyone sounds comfortably together, from the grandest gestures to the most intimate moments. Curzon glides through the first-movement Maestoso with the appropriate measure of majesty, yet with a delicate lyricism as well, and Szell seems perfectly attuned to the pianist’s every mood and need.

In the second-movement Adagio Curzon again finds his range, although his pace is a tad more leisurely than other pianists of my experience. However, his step is never loose or slack, merely relaxed. The playing is quite lovely, the movement said to be an elegiac tribute to Brahms’s late mentor, Robert Schumann. Then, Curzon and company go out on a agreeably jubilant note in the finale, a spirited peasant dance with variations that sparkles with good cheer.

John J. Puccio

May 28, 2014