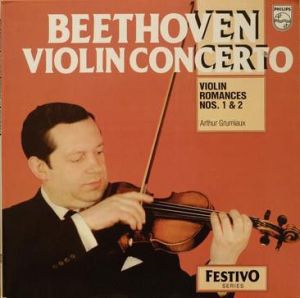

More of the music of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

More Hot Stamper Pressings Featuring the Violin

The reproduction of the violin here is superb — harmonically rich, natural, clean, clear, resolving. What sets the truly killer pressings apart is the depth, width and three-dimensional quality of the sound, as well as the fact that they become less congested in the louder passages and don’t get shrill or blary. The best copies display a Tubey Magical richness — especially evident in the basses and celli — that is to die for.

Big space, a solid bottom, and plenty of dynamic energy are strongly in evidence throughout. Exceptional resolution, transparency, tremendous dynamics, a violin that is present and solid — this copy takes the sound of the recording right to the limits of what we thought possible from Philips.

As we listened, we became completely immersed in the music, transfixed by the remarkable virtuosity he brings to such a difficult and demanding work.

What to Listen For

This copy had very little smear on either the violin or the orchestra. Try to find a violin concerto record with no smear.

Let’s face it: records from every era more often than not have some smear and we can never really know what accounts for it. The key thing is to be able to recognize it for what it is. (We find modern records, especially those pressed at RTI, to be quite smeary as a rule. They also tend to be congested, blurry, thick, veiled, and ambience-challenged. For some reason most audiophiles — and the reviewers who write for them — rarely seem to notice these shortcomings.)

Of course, if your system itself has smear — practically every tube system I have ever heard has some smear, including the one I used to own — it becomes harder to hear smear on your records.

Our all transistor rig has no trouble showing it to us.

Keep in mind that one thing live music never has is smear of any kind. Live music is scompletely mear-free. It can be harmonically distorted, hard, edgy, thin, fat, dark, and all the rest, but one thing it never is, is smeary.

That is a shortcoming unique to the imperfect reproduction of music, and one for which many of the pressings we sell are downgraded.

- Here are more recordings that are good for testing smear.

- Here are some records with a tendency to have smeary sound

Side One

Allegro, Ma Non Troppo

Larghetto

Side Two

Rondo

Violin Romance No. 1 In G, Op. 40

Violin Romance No. 2 In F, Op.50

Description by Michael Rodman

Beethoven wrote his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61 (1806), at the height of his so-called “second” period, one of the most fecund phases of his creativity. The violin concerto represents a continuation — indeed, one of the crowning achievements — of Beethoven’s exploration of the concerto, a form he would essay only once more, in the Piano Concerto No. 5 (1809).

By the time of the violin concerto, Beethoven had employed the violin in concertante roles in a more limited context. Around the time of the first two symphonies, he produced two romances for violin and orchestra; a few years later, he used the violin as a member of the solo trio in the Triple Concerto (1803-1804). These works, despite their musical effectiveness, must still be regarded as studies and workings-out in relation to the violin concerto, which more clearly demonstrates Beethoven’s mastery in marshalling the distinctive formal and dramatic forces of the concerto form.

Characteristic of Beethoven’s music, the dramatic and structural implications of the concerto emerge at the outset, in a series of quiet timpani strokes that led some early detractors to dismiss the work as the “Kettledrum Concerto.” Striking as it is, this fleeting, throbbing motive is more than just an attention-getter; indeed, it provides the very basis for the melodic and rhythmic material that is to follow.

At over 25 minutes in length, the first movement is notable as one of the most extended in any of Beethoven’s works, including the symphonies. Its breadth arises from Beethoven’s adoption of the Classical ritornello form — here manifested in the extended tutti that precedes the entrance of the violin — and from the composer’s expansive treatment of the melodic material throughout.

The second movement takes a place among the most serene music Beethoven ever produced. Free from the dramatic unrest of the first movement, the second is marked by a tranquil, organic lyricism. Toward the end, an abrupt orchestral outburst leads into a cadenza, which in turn takes the work directly into the final movement. The genial Rondo, marked by a folk-like robustness and dancelike energy, makes some of the work’s more virtuosic demands on the soloist.

NPR Guide

What sets the Violin Concerto apart from previous works in the genre is the integration of the solo part within the orchestral fabric, the fusion of violin and orchestra into something far beyond the conventional 18th-century notion of the concerto as a mere solo-tutti confrontation.

The violin is still given the opportunity to do what it does best on a grand scale — namely, to sing. Yet the concerto’s most telling moments are its quietest, where Beethoven speaks not as the thunderer, but as the “still, small voice,” taking advantage of the solo instrument’s marvelous expressiveness in soft dynamics — as when the violin emerges from the first-movement cadenza playing the gentle second subject on its two lower strings, over a hushed pizzicato accompaniment.

This is an Older Classical/Orchestral Review

Most of the older reviews you see are for records that did not go through the shootout process, the revolutionary approach to finding better sounding pressings we started developing in the early 2000s and have since turned into a veritable science.

We found the records you see in these older listings by cleaning and playing a pressing or two of the album, which we then described and priced based on how good the sound and surfaces were. (For out Hot Stamper listings, the Sonic Grades and Vinyl Playgrades are listed separately.)

We were often wrong back in those days, something we have no reason to hide. Audio equipment and record cleaning technologies have come a long way since those darker days, a subject we discuss here.

Currently, 99% (or more!) of the records we sell are cleaned, then auditioned under rigorously controlled conditions, up against a number of other pressings. We award them sonic grades, and then condition check them for surface noise.

As you may imagine, this approach requires a great deal of time, effort and skill, which is why we currently have a highly trained staff of about ten. No individual or business without the aid of such a committed group could possibly dig as deep into the sound of records as we have, and it is unlikely that anyone besides us could ever come along to do the kind of work we do.

The term “Hot Stampers” gets thrown around a lot these days, but to us it means only one thing: a record that has been through the shootout process and found to be of exceptionally high quality.

The result of our labor is the hundreds of titles seen here, every one of which is unique and guaranteed to be the best sounding copy of the album you have ever heard or you get your money back.

Further Reading