More of the music of Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

More Classical Masterpieces

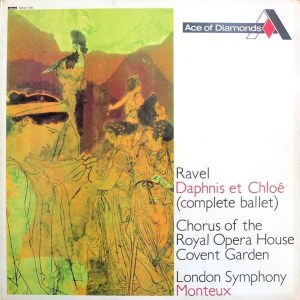

- Boasting excellent Double Plus (A++) grades or close to them throughout, this vintage Decca Ace of Diamonds pressing was giving us the sound we were looking for on Ravel’s complete Masterpiece

- The sound is big and rich, lively and open, with tons of depth and huge climaxes that hold together (particularly on side one)

- The voices in the chorus are clear, natural, separate and full-bodied — this is the hallmark of a vintage Golden Age recording: naturalness

- We know of no other recording of the work that does as good a job of capturing such a large orchestra and chorus

- Of course, Monteux is a master of the French idiom – his performance of the complete ballet is definitive in our opinion

- Even though properly-cleaned, properly-pressed, properly-mastered original Decca pressings are the ones that win our shootouts, we guarantee this 60s reissue will easily beat any copy of the album you can find, at any price

- There are about 150 orchestral recordings we have found to offer the best performances with the highest quality sound. As card-carrying audiophiles, we naturally insist on both. This record is certainly deserving of a place on that list.

Both sides here are BIG, with the space and depth of the wonderful Kingsway Hall that the LSO perform in. John Culshaw produced the album, which surely accounts for the huge size and space, not to mention quality, of the recording. The sound is dynamic and tonally correct throughout.

This vintage Decca pressing has the kind of Tubey Magical Midrange that modern records can barely BEGIN to reproduce. Folks, that sound is gone and it sure isn’t showing signs of coming back. If you love hearing INTO a recording, actually being able to “see” the performers, and feeling as if you are sitting in the studio with the band, this is the record for you. It’s what vintage all analog recordings are known for — this sound.

If you exclusively play modern repressings of vintage recordings, I can say without fear of contradiction that you have never heard this kind of sound on vinyl. Old records have it — not often, and certainly not always — but maybe one out of a hundred new records do, and those are some pretty long odds.

What The Best Sides Of Daphnis et Chloé Have To Offer Is Not Hard To Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1959

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

Copies with rich lower mids and nice extension up top did the best in our shootout, assuming they weren’t veiled or smeary of course. So many things can go wrong on a record! We know, we’ve heard them all.

Top end extension is critical to the sound of the best copies. Lots of old records (and new ones) have no real top end; consequently, the studio or stage will be missing much of its natural air and space, and instruments will lack their full complement of harmonic information.

Tube smear is common to most vintage pressings. The copies that tend to do the best in a shootout will have the least (or none), yet are full-bodied, tubey and rich.

What We’re Listening For On Daphnis et Chloé

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Powerful bass — which ties in with good transient information, also the issue of frequency extension further down.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

Vinyl Condition

Mint Minus Minus and maybe a bit better is about as quiet as any vintage pressing will play, and since only the right vintage pressings have any hope of sounding good on this album, that will most often be the playing condition of the copies we sell. (The copies that are even a bit noisier get listed on the site are seriously reduced prices or traded back in to the local record stores we shop at.)

Those of you looking for quiet vinyl will have to settle for the sound of other pressings and Heavy Vinyl reissues, purchased elsewhere of course as we have no interest in selling records that don’t have the vintage analog magic of these wonderful recordings.

If you want to make the trade-off between bad sound and quiet surfaces with whatever Heavy Vinyl pressing might be available, well, that’s certainly your prerogative, but we can’t imagine losing what’s good about this music — the size, the energy, the presence, the clarity, the weight — just to hear it with less background noise.

The Monteux Era

by Thomas Simone

Monteux’s performance of Ravel’s masterpiece, Daphnis and Chloe is legendary. Monteux studied the score with Ravel and conducted the première of the ballet in 1912. John Culshaw produced the recording in 1959 for Decca with a sense of special occasion, and the recorded performance in very fine sound by Alan Reeve shows a common artistic purpose (London CS 6147/Decca SXL 2164).

Partly because of the need to place the entire score on a single disc, the recording is cut at a slightly low volume. Also the performance setting is larger and more reverberant than is usual for Decca. This perspective, however, works wonderfully with Monteux’s vision of Ravel’s mythic world of Mediterranean shepherds, shepherdesses, and pirates. Monteux’s characteristics show brilliantly in his instrumental balance and sense of delicacy, his mastery of the work’s shape, and his narrative understanding of the ballet.

Most important and moving of all is Monteux’s love of the music. We have few performances on record sound that offer the beauty, insight, and joy of Monteux’s sublime Daphnis and Chloe

Notes on Daphnis et Chloé from The Kennedy Center

Daphnis et Chloé, generally regarded as Ravel’s masterpiece, is one of the numerous important scores that owe their existence to the famous ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was just beginning to commission new works for his Paris-based troupe in 1909. One of the composers he signed that year was the virtually unknown 27-year-old Igor Stravinsky, who became an international celebrity virtually overnight with the premiere of his Firebird the following year. At the same time Diaghilev contacted Stravinsky, he invited Ravel to compose the music for Daphnis et Chloé.

Ravel described his score as “a choreographic symphony in three parts, “in which his intention “was to compose a vast musical fresco, less scrupulous as to archaism than faithful to the Greece of my dreams, which inclined readily enough to what French artists of the late eighteenth century imagined and depicted.” He wrote for a sumptuously large orchestra plus a wind machine and a wordless chorus at various points.

Notes from The Kennedy Center

Ravel began composing his score for Daphnis et Chloé in 1909 and completed it in 1912. In 1911 he extracted a brief concert suite from the portion of the work he had completed by then, and it was performed by the Colonne Orchestra under Gabriel Pierné on April 2 of that year; the very successful Suite No. 2 was produced two years later. In the meantime the premiere of the ballet was given by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes at the Théâtre du Châtelet on June 8, 1912, with choreography by Michel Fokine and décor by Léon Bakst; Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina danced the title roles, and the conductor was Pierre Monteux. The National Symphony Orchestra first performed music from Daphniset Chloé on October 30, 1938, when Hans Kindler conducted the Suite No. 2, and performed that suite most recently on September 24, 2205, under Leonard Slatkin. Antal Doráti conducted the orchestra’s first performances of the full ballet score, on January 28-30, 1975; Barry Jekowsky conducted the most recent ones, on January 23-25, 1997.

The score calls for 3 flutes and 2 piccolos, 3 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, tambourine, wind machine, celesta, 2 harps, strings, and a wordless chorus. Duration, 55 minutes.

Daphnis et Chloé, generally regarded as Ravel’s masterpiece, is one of the numerous important scores that owe their existence to the famous ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was just beginning to commission new works for his Paris-based troupe in 1909. One of the composers he signed that year was the virtually unknown 27-year-old Igor Stravinsky, who became an international celebrity virtually overnight with the premiere of his Firebird the following year. At the same time Diaghilev contacted Stravinsky, he invited Ravel to compose the music for Daphnis et Chloé.

Seven years older than Stravinsky and a good deal more widely known, Ravel had written little for orchestra at that time. He was eager to work with Diaghilev, but insisted on revising the scenario Michel Fokine had written for Daphnis et Chloé. He had his piano score ready in 1910, but the orchestration went slowly; the concluding Danse générale was subjected to so many revisions that Ravel said he put in a full year’s work on that section alone.

During the three years in which Ravel was struggling with the orchestration of Daphnis et Chloé, Diaghilev produced not only The Firebird but also Stravinsky’s second and more remarkable ballet, Petrushka, and during the same period Ravel himself orchestrated two of his own piano compositions–the suite Ma Mère l’Oye and the Valses nobles et sentimentales–for use in ballets, both of which were staged before Daphnis was. As already noted, the first of the two concert suites from Daphnis was actually performed a year before Ravel completed the later portions of the ballet score. He finally accomplished that on April 5, 1912, barely two months before the staged premiere.

The scenario for the ballet, as prepared by Fokine and subsequently revised by Ravel, was adapted from a pastoral tale ascribed to an early Greek poet named Longus: Daphnis and Chloe, both abandoned in infancy on the island of Lesbos, have been brought up by benevolent shepherd folk. They fall in love, and Daphnis teaches Chloe to play the pipes he fashions from reeds. Chloe is abducted by priates, but is rescued by the great god Pan, and restored to Daphnis amid general rejoicing. (This Greek tale was translated into both French and English in the sixteenth century; there were several subsequent translations, and a number of musical consequences, one of the earliest still surviving being a charming opera-ballet composed by Joseph Bodin de Boismortier in 1747.)

Ravel described his score as “a choreographic symphony in three parts, “in which his intention “was to compose a vast musical fresco, less scrupulous as to archaism than faithful to the Greece of my dreams, which inclined readily enough to what French artists of the late eighteenth century imagined and depicted.” He wrote for a sumptuously large orchestra plus a wind machine and a wordless chorus at various points. To accommodate Diaghilev, he prepared an alternative version in which the voices are replaced by instrumental doublings; but he issued a public objection to Diaghilev’s presentation of the work in London without the chorus in 1914.

For many years the only portions of this score performed in concerts and recordings were the two concert suites, which, according to Ravel’s pupil, confidant and biographer Alexis Roland-Manuel, “contain . . . the essential and best-written parts of the work.” Ravel himself, however, noted in his Autobiographical Sketch (1928), that his “choreographic symphony” is so constructed that even without the stage action it makes more sense when performed in full. “The work,” he wrote, “is constructed symphonically according to a strict tonal play by the method of a few motifs, the development of which achieves a symphonic homogeneity of style.” Listeners familiar only with the celebrated Suite No. 2 will recognize several of the themes, or their roots, in the first part of the complete score, and will be able to follow their development easily enough through the subtle metamorphoses corresponding to scenes in the stage action.