More of the music of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

More Recordings Featuring the Violin

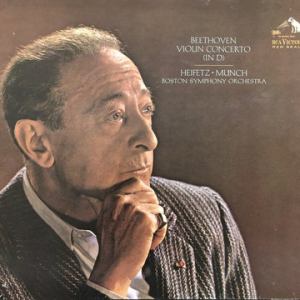

- Our outstanding vintage pressing of this brilliant Living Stereo recording — from 1956! — boasts solid Double Plus (A++) sound throughout

- It’s also fairly quiet at Mint Minus Minus, a grade that even our most well-cared-for vintage classical titles have trouble playing at

- Heifetz’s violin is immediate, real and lively here – you are in the presence of greatness with this recording

- The orchestra is wide, tall, spacious, rich and tubey, yet the dynamics and transparency are first rate

- White Dogs and Shaded Dogs can both sound quite good on this title – just avoid the Red Seals and later pressings if you are looking for the best sound

The reproduction of the violin here is superb — harmonically rich, natural, clean, clear, resolving. What sets the truly killer pressings apart is the depth, width and three-dimensional quality of the sound, as well as the fact that they become less congested in the louder passages and don’t get shrill or blary.

The best copies display a Tubey Magical richness — especially evident in the basses and celli — that is to die for.

Big space, a solid bottom, and plenty of dynamic energy are strongly in evidence throughout. Little smear, exceptional resolution, transparency, tremendous dynamics, a violin that is present and solid — the best copies take the sound of the recording right to the limits of what we thought possible.

Heifetz is a fiery player. On a good pressing such as this one, you will hear all the detail of his bowing without being overpowered by it. As we listened we became completely immersed in the music on the record, transfixed by the remarkable virtuosity he brings to such a difficult and demanding work.

Avoiding the Smear

This copy had practically no smear on either the violin or the orchestra. Try to find a violin concerto record with no smear. We often say that Shaded Dogs, being vintage All Tube recordings, tend to have tube smear. But what about the ’70s Transistor Mastered Red Label pressings – where does their smear come from?

Let’s face it: records from every era more often than not have some smear and we can never really know what accounts for it. The key thing is to be able to recognize it for what it is. (We find modern records, especially those pressed at RTI, to be quite smeary as a rule. They also tend to be congested, blurry, thick, veiled, and ambience-challenged. For some reason most audiophiles — and the reviewers who write for them — rarely seem to be bothered by these shortcomings, if they notice them at all.)

Of course, if your system itself has smear — practically every tube system I have ever heard has some smear; it comes with the territory — it becomes harder to hear smear on your records. Our current all-transistor rig has no trouble showing it to us.

Keep in mind that one thing live music never has is smear of any kind. Live music is smear-free. It can be harmonically distorted, hard, edgy, thin, fat, dark, and fail in any number of other ways, but one thing it never is, is smeary. That is a shortcoming unique to the reproduction of music, and one for which many of the pressings we sell are downgraded.

What the Best Sides of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto Have to Offer Is Not Hard to Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1956

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

What We’re Listening For on This Wonderful Classical Release

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

A Must Own Violin Recording by a True Master

This wonderful violin concerto — one of the greatest ever composed — should be part of any serious Living Stereo Classical Collection.

Others that belong in that category can be found here.

Side One

Allegro, Ma Non Troppo

Side Two

Larghetto

Rondo

The Violin Concerto in D Major

Description by Michael Rodman

Beethoven wrote his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61 (1806), at the height of his so-called “second” period, one of the most fecund phases of his creativity. The violin concerto represents a continuation — indeed, one of the crowning achievements — of Beethoven’s exploration of the concerto, a form he would essay only once more, in the Piano Concerto No. 5 (1809).

By the time of the violin concerto, Beethoven had employed the violin in concertante roles in a more limited context. Around the time of the first two symphonies, he produced two romances for violin and orchestra; a few years later, he used the violin as a member of the solo trio in the Triple Concerto (1803-1804). These works, despite their musical effectiveness, must still be regarded as studies and workings-out in relation to the violin concerto, which more clearly demonstrates Beethoven’s mastery in marshalling the distinctive formal and dramatic forces of the concerto form.

Characteristic of Beethoven’s music, the dramatic and structural implications of the concerto emerge at the outset, in a series of quiet timpani strokes that led some early detractors to dismiss the work as the “Kettledrum Concerto.” Striking as it is, this fleeting, throbbing motive is more than just an attention-getter; indeed, it provides the very basis for the melodic and rhythmic material that is to follow.

At over 25 minutes in length, the first movement is notable as one of the most extended in any of Beethoven’s works, including the symphonies. Its breadth arises from Beethoven’s adoption of the Classical ritornello form — here manifested in the extended tutti that precedes the entrance of the violin — and from the composer’s expansive treatment of the melodic material throughout.

The second movement takes a place among the most serene music Beethoven ever produced. Free from the dramatic unrest of the first movement, the second is marked by a tranquil, organic lyricism. Toward the end, an abrupt orchestral outburst leads into a cadenza, which in turn takes the work directly into the final movement. The genial Rondo, marked by a folk-like robustness and dancelike energy, makes some of the work’s more virtuosic demands on the soloist.

NPR Guide

What sets the Violin Concerto apart from previous works in the genre is the integration of the solo part within the orchestral fabric, the fusion of violin and orchestra into something far beyond the conventional 18th-century notion of the concerto as a mere solo-tutti confrontation.

The violin is still given the opportunity to do what it does best on a grand scale — namely, to sing. Yet the concerto’s most telling moments are its quietest, where Beethoven speaks not as the thunderer, but as the “still, small voice,” taking advantage of the solo instrument’s marvelous expressiveness in soft dynamics — as when the violin emerges from the first-movement cadenza playing the gentle second subject on its two lower strings, over a hushed pizzicato accompaniment.