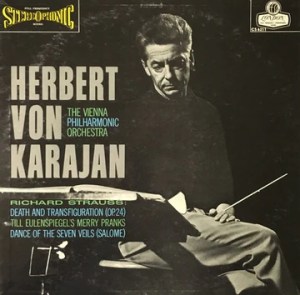

More of the music of Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

More Imported Pressings on Decca and London

- This original Stereo London pressing of Karajan and the Vienna Phil’s performance of these classical pieces boasts stunning Nearly Triple Plus (A++ to A+++) sound from first note to last – just shy of our Shootout Winner

- It’s also fairly quiet at Mint Minus Minus, a grade that even our most well-cared-for vintage classical titles have trouble playing at

- These are superb readings of the works, and we know of no others that can compete with the sound of this Decca recording

- Clear, transparent, rich, big, spacious, tonally correct, with Tubey Magical textured strings, this record is doing practically everything right, and that makes it a very special pressing indeed

- Some old record collectors (like me) say classical recording quality ain’t what it used to be – here’s all the proof anyone with two working ears and top quality audiophile equipment needs to make the case

This vintage London pressing has the kind of Tubey Magical Midrange that modern records can barely BEGIN to reproduce. Folks, that sound is gone and it sure isn’t showing signs of coming back. If you love hearing INTO a recording, actually being able to “see” the performers, and feeling as if you are sitting in the studio with the band, this is the record for you. It’s what vintage all analog recordings are known for — this sound.

If you exclusively play modern repressings of vintage recordings, I can say without fear of contradiction that you have never heard this kind of sound on vinyl. Old records have it — not often, and certainly not always — but maybe one out of a hundred new records do, and those are some pretty long odds.

What The Best Sides Of CS 6211 Have To Offer Is Not Hard To Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1961

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

Copies with rich lower mids and nice extension up top did the best in our shootout, assuming they weren’t veiled or smeary of course. So many things can go wrong on a record! We know, we’ve heard them all.

Top end extension is critical to the sound of the best copies. Lots of old records (and new ones) have no real top end; consequently, the studio or stage will be missing much of its natural air and space, and instruments will lack their full complement of harmonic information.

Tube smear is common to most vintage pressings. The copies that tend to do the best in a shootout will have the least (or none), yet are full-bodied, tubey and rich.

A Big Group of Musicians Needs This Kind of Space

One of the qualities that we don’t talk about on the site nearly enough is the SIZE of the record’s presentation. Some copies of the album just sound small — they don’t extend all the way to the outside edges of the speakers, and they don’t seem to take up all the space from the floor to the ceiling. In addition, the sound can often be recessed, with a lack of presence and immediacy in the center.

Other copies — my notes for these copies often read “BIG and BOLD” — create a huge soundfield, with the music positively jumping out of the speakers. They’re not brighter, they’re not more aggressive, they’re not hyped-up in any way, they’re just bigger and clearer.

And most of the time those very special pressings are just plain more involving. When you hear a copy that does all that — a copy like this one — it’s an entirely different listening experience.

What We’re Listening For On CS 6211

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Powerful bass — which ties in with good transient information, also the issue of frequency extension further down.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

Side One

Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Op. 28

Dance Of The Seven Veils (“Salome”)

Side Two

Tod Und Verklärung (Death And Transfiguration), Op. 24

Death and Transfiguration

Death and Transfiguration (German: Tod und Verklärung), Op. 24, is a tone poem for orchestra by Richard Strauss. Strauss began composition in the late summer of 1888 and completed the work on 18 November 1889. The work is dedicated to the composer’s friend Friedrich Rosch.

The music depicts the death of an artist. At Strauss’s request, this was described in a poem by his friend Alexander Ritter as an interpretation of Death and Transfiguration, after it was composed. As the man lies dying, thoughts of his life pass through his head: his childhood innocence, the struggles of his manhood, the attainment of his worldly goals; and at the end, he receives the longed-for transfiguration “from the infinite reaches of heaven.”

Performance history

Strauss conducted the premiere on 21 June 1890 at the Eisenach Festival (on the same programme as the premiere of his Burleske in D minor for piano and orchestra). He also conducted this work for his first appearance in the United Kingdom, at the Wagner Concert with the Philharmonic Society on 15 June 1897 at the Queen’s Hall in London.

Critical reaction

English music critic Ernest Newman described this as music to which one would not want to die or awaken. “It is too spectacular, too brilliantly lit, too full of pageantry of a crowd; whereas this is a journey one must make very quietly, and alone.”

French critic Romain Rolland in his Musiciens d’aujourd’hui (1908) called the piece “one of the most moving works of Strauss, and that which is constructed with the noblest utility.”

Structure

There are four parts (with Ritter’s poetic thoughts condensed):

- Largo (The sick man, near death)

- Allegro molto agitato (The battle between life and death offers no respite to the man)

- Meno mosso (The dying man’s life passes before him)

- Moderato (The sought-after transfiguration)

A typical performance lasts about 25 minutes.

In one of his last compositions, “Im Abendrot” from the Four Last Songs, Strauss poignantly quotes the “transfiguration theme” from his tone poem of 60 years earlier, during and after the soprano’s final line, “Ist dies etwa der Tod?” (Is this perhaps death?).

Just before his own death, he remarked that his music was absolutely correct; his feelings mirrored those of the artist depicted within; Strauss said to his daughter-in-law as he lay on his deathbed in 1949: “It’s a funny thing, Alice, dying is just the way I composed it in Tod und Verklärung.”

-Wikipedia