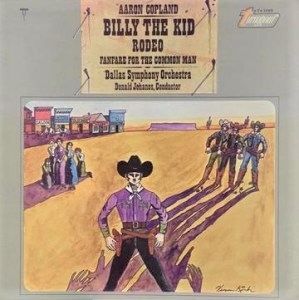

More Classical Masterpieces

More Orchestral Spectaculars

- You’ll find solid Double Plus (A++) sound throughout this Copland Masterpiece – reasonably quiet vinyl too (noted condition issue notwithstanding), with no audible marks and no Inner Groove Distortion (IGD)

- A spectacular Demo Disc recording that is clear, rich, dynamic, transparent and energetic – here is the big, bold sound we love

- The labels are reversed on this copy

- “To the ultimate delight of audiences Copland managed to weave musical complexity with popular style.”

- If you’re a fan of orchestral showpieces such as these, this recording from 1967 belongs in your collection.

This vintage Turnabout pressing has the kind of Tubey Magical Midrange that modern records can barely BEGIN to reproduce. Folks, that sound is gone and it sure isn’t showing signs of coming back. If you love hearing INTO a recording, actually being able to “see” the performers, and feeling as if you are sitting in the studio with the band, this is the record for you. It’s what vintage all analog recordings are known for —this sound.

If you exclusively play modern repressings of vintage recordings, I can say without fear of contradiction that you have never heard this kind of sound on vinyl. Old records have it — not often, and certainly not always — but maybe one out of a hundred new records do, and those are some pretty long odds.

What the Best Sides of Billy The Kid Have to Offer Is Not Hard to Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1967

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

Copies with rich lower mids and nice extension up top did the best in our shootout, assuming they weren’t veiled or smeary of course. So many things can go wrong on a record! We know, we’ve heard them all.

Top end extension is critical to the sound of the best copies. Lots of old records (and new ones) have no real top end; consequently, the studio or stage will be missing much of its natural air and space, and instruments will lack their full complement of harmonic information.

Tube smear is common to most vintage pressings and this is no exception. The copies that tend to do the best in a shootout will have the least (or none), yet are full-bodied, tubey and rich.

What We’re Listening For on Billy The Kid / Rodeo / Fanfare For The Common Man

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

A Must Own Classical Record

This Demo Disc Quality recording should be part of any serious Classical Music Collection. Others that belong in that category can be found here.

Side One

Fanfare For The Common Man

Four Dance Episodes From “Rodeo”

Buckaroo Holiday

Corral Nocturne

Saturday Night Waltz

Hoe-Down

Side Two

Billy The Kid (Ballet Suite)

The Library Of Congress On Fanfare for the Common Man

“Fanfare for the Common Man” was certainly Copland’s best known concert opener. He wrote it in response to a solicitation from Eugene Goosens for a musical tribute honoring those engaged in World War II. Goosens, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, originally had in mind a fanfare “… for Soldiers, or for Airmen or Sailors” and planned to open his 1942 concert season with it.

Aaron Copland later wrote, “The challenge was to compose a traditional fanfare, direct and powerful, yet with a contemporary sound.” To the ultimate delight of audiences Copland managed to weave musical complexity with popular style. He worked slowly and deliberately, however, and the piece was not ready until a full month after the proposed premier.

To Goosens’ surprise Copland titled the piece “Fanfare for the Common Man” (although his sketches show he also experimented with other titles such as “Fanfare for a Solemn Ceremony” and “Fanfare for Four Freedoms”). Fortunately Goosens loved the work, despite his puzzlement over the title, and decided with Copland to preview it on March 12, 1943. As income taxes were to be paid on March 15 that year, they both felt it was an opportune moment to honor the common man. Copland later wrote, “Since that occasion, ‘Fanfare’ has been played by many and varied ensembles, ranging from the U.S. Air Force Band to the popular Emerson, Lake, and Palmer group … I confess that I prefer ‘Fanfare’ in the original version, and I later used it in the final movement of my Third Symphony.”

Aaron Copland, said the composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, was the one to “lead American music out of the wilderness.” Copland’s musical opus, for which he received the 1964 Medal of Freedom, also included such masterworks as “Piano Variations” (1930), “El Salon Mexico” (1936), “Billy the Kid” (1938), “Fanfare for the Common Man” (1942), “Rodeo” (1942), “Appalachian Spring” (1944), and “Inscape” (1967).

AMG Bio – Aaron Copland

Few figures in American music loom as large as Aaron Copland. As one of the first wave of literary and musical expatriates in Paris during the 1920s, Copland returned to the United States with the means to assume, for the next half century, a central role in American music as composer, promoter, and educator. Copland’s sheer popularity and iconic status are such that his music has transcended the concert hall and entered the popular consciousness; it both accompanies solemn and joyous celebrations the world over (Fanfare for the Common Man) and punctuates the familiar words “Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner!” (Rodeo) for millions of television viewers.

Copland was the youngest of five children born to Harris and Sarah Copland, Lithuanian Jewish immigrants who owned a department store in Brooklyn. He did not take formal piano lessons until he was 13, by which time he had also begun writing small pieces. Instead of attending college, Copland studied theory and composition with Rubin Goldmark and piano with Victor Wittgenstein and Clarence Adler, and attended as many concerts, operas, and ballets as possible.

In 1921, he went to Fontainebleau, France, taking conducting and composition classes at the American Conservatory. He went on to study in Paris with Ricardo Viñes and Nadia Boulanger and spent the next three years soaking up all the European culture, both new and old, that he could. He learned to admire not only composers like Stravinsky, Milhaud, Fauré, and Mahler, but others such as author André Gide. Boulanger’s performance of Copland’s 1924 Organ Symphony with Koussevitzky was the beginning of a friendship between the conductor and composer that led to Copland teaching at the Berkshire Music Center (Tanglewood) from 1940 until 1965.

After his return to America, Copland drifted toward an incisive, austere style that captured something of the sobriety of Depression-torn America. The most representative work of this period — the Piano Variations (1930) — remains one of the composer’s seminal efforts. He tried to avoid taking a university position, instead writing for journals and newspapers, organizing concerts, and taking on administrative duties for composers’ organizations, trying to promote American music.

By the mid-1930s, taking the direct engagement of and communication with audiences as one of his central tenets, Copland’s compositions developed (in parallel with other composers like Virgil Thomson and Roy Harris) an “American” style marked by folk influences, a new melodic and harmonic simplicity, and an appealing directness free from intellectual pretension. This is nowhere more in evidence than in Copland’s ballets of this period, and it finally earned him the respect of the general public.

While Copland gradually became less prolific from the mid-1950s on, he continued to experiment and explore “fresh” means of musical expression, including a highly individual adoption of 12-tone principles in works like the Piano Fantasy and Connotations for orchestra. Still, the fundamentally lyrical nature of Copland’s language remained intact and occasionally emerged — with an often surprising retrospective air — in works like the Duo for flute and piano (1971). He continued to teach and write and received numerous awards both in America and abroad.

In 1958, he began conducting orchestras around the world, performing works by 80 other composers as well as his own over the next 20 years. By the mid-’70s, Copland had for all intents and purposes ceased composing. One of the last of his creative accomplishments was the completion of his two-volume autobiography (with musicologist Vivian Perlis), an essential document in understanding the growth of American music in the twentieth century.