More of the music of Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

More music conduced by Ernest Ansermet

- Outstanding Double Plus (A++) sound throughout this vintage London pressing of Ansermet and the Suisse Romande’s superb performance of this dazzlingly symphonic suite

- It’s also fairly quiet at Mint Minus Minus, a grade that even our most well-cared-for vintage classical titles have trouble playing at

- This copy will go head to head with the hottest Reiner pressing and is guaranteed to blow the doors off of it

- The top end is natural and sweet – this is the way the solo violin in the left channel is supposed to sound

- Extraordinary Demo Disc sound – the brass displays weight and power throughout the powerful first movement like nothing you’ve ever heard in your life, outside of a live performance of course

- Finding the best sounding pressings of this exceptional recording was a breakthrough for us – here was sound we had never experienced for the work, and let me tell you, that was a thrill we will not soon forget

- These are the stampers that always win our shootouts, and when you play this copy, you will know why – the sound is big, rich and clear like no other Scheherazade you’ve heard

- We’ve come up with a simple listening test to help our audiophile brethren judge pressings of Scheherazade, especially those woeful iterations of the music on Heavy Vinyl. We hope you will find time to avail yourself ofthe lessons we’ve learned

- There are about 80 orchestral recordings that are personal favorites, and this one deserves a place right at the top of that list

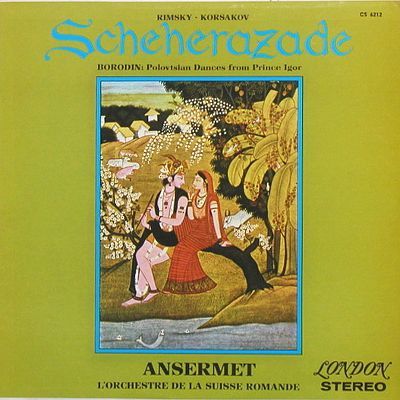

We did a monster shootout for this music in 2014, one we had been planning for more than two years. On hand were quite a few copies of the Reiner on RCA; the Ansermet on London (CS 6212, his second stereo recording, from 1961, not the earlier and noticeably poorer sounding recording from in 1959); the Ormandy on Columbia, and a few others we felt had potential.

The only recordings that held up all the way through — the fourth movement being THE Ball Breaker of all time, for both the engineers and musicians — were those by Reiner and Ansermet. This was disappointing considering how much time and money we spent finding, cleaning and playing those ten or so other pressings.

Here it is many years later and we’re capitalizing on what we learned from the first big go around, which is simply this: the Ansermet recording on Decca/London can not only hold its own with the Reiner on RCA, but beat it in virtually every area. The presentation and the sound itself are both more relaxed and natural, even when compared to the best RCA pressings.

The emotional content of the first three movements (all of side one) under Ansermet’s direction are clearly superior. The roller-coaster excitement Reiner and the CSO bring to the fourth movement cannot be faulted, or equaled. In every other way, Ansermet’s performance is the one for me. We did a monster shootout for this music in 2014, one we had been planning for more than two years. On hand were quite a few copies of the Reiner on RCA; the Ansermet on London (CS 6212, his second stereo recording, from 1961, not the earlier and noticeably poorer sounding recording from in 1959); the Ormandy on Columbia, and a few others we felt had potential.

Production and Engineering

James Walker was the producer, Roy Wallace the engineer for these sessions from April of 1959 in Geneva’s glorious Victoria Hall. It’s yet another remarkable disc from the Golden Age of Vacuum Tube Recording.

The hall the Suisse Romande recorded in was possibly the best recording venue of its day, possibly of all time. More amazing sounding recordings were made there than in any other hall we know of. There is a solidity and richness to the sound beyond all others, yet clarity and transparency are not sacrificed in the least.

It’s as wide, deep and three-dimensional as any, which is of course all to the good, but what makes the sound of these recordings so special is the weight and power of the brass, combined with unerring timbral accuracy of the instruments in every section of the orchestra.

What the Best Sides of Scheherazade Have to Offer Is Not Hard to Hear

- The biggest, most immediate staging in the largest acoustic space

- The most Tubey Magic, without which you have almost nothing. CDs give you clean and clear. Only the best vintage vinyl pressings offer the kind of Tubey Magic that was on the tapes in 1961

- Tight, note-like, rich, full-bodied bass, with the correct amount of weight down low

- Natural tonality in the midrange — with all the instruments having the correct timbre

- Transparency and resolution, critical to hearing into the three-dimensional studio space

No doubt there’s more but we hope that should do for now. Playing the record is the only way to hear all of the qualities we discuss above, and playing the best pressings against a pile of other copies under rigorously controlled conditions is the only way to find a pressing that sounds as good as this one does.

The Sound

Big brass, so full-bodied and dynamic, yet clear and not thick or overly tubey. Lots of space as is usually the case with Ansermet’s recordings from this era.

These two sides are BIG, with the space and depth of the wonderful Victoria Hall that the L’Orchestre De La Suisse Romande perform in. As a rule, the classic ’50s and ’60s recordings of Ansermet and the Suisse Romande are as big and rich as any you’ve heard. On the finest pressings (known around these parts as Hot Stampers) they seem to be the ideal blend of clarity and richness, with depth and spaciousness that will put to shame 98% of the classical recordings ever made.

The solo violin is present and so real you will have a hard time believing it.

These copies are huge in every dimension, just as all the best ones always are, with maximum amounts of height, width, and depth. The transparency is also superb — you really hear into this one in the way that only the best Golden Age recordings allow.

Side Two Coupling Work

Borodin: Prince Igor – Polovtsian Dances

Although we did not listen specifically to the Borodin that takes up about half of side two — only the last movement of Scheherazade is on side two — we did hear wonderful sound coming from some of the copies we played, meaning simply that we feel the work is well-recorded.

What We’re Listening For on Scheherazade

- Energy for starters. What could be more important than the life of the music?

- The Big Sound comes next — wall to wall, lots of depth, huge space, three-dimensionality, all that sort of thing.

- Then transient information — fast, clear, sharp attacks, not the smear and thickness so common to these LPs.

- Next: transparency — the quality that allows you to hear deep into the soundfield, showing you the space and air around all the instruments.

- Extend the top and bottom and voila, you have The Real Thing — an honest to goodness Hot Stamper.

Awful Shaded Dogs

The somewhat shocking news is just how awful most Shaded Dog copies are. Even the ones with the “right” stampers are often far from what they should be. It is my heretical opinion that only one or two out of ten copies of the RCA vinyl will beat the Living Stereo CD, and no reissue of any kind can touch it. The CD sounds right. Most vinyl pressings do not.

As is so often the case, hearing the phenomenally good pressings made all the time and effort we put into the shootout worthwhile. Our top Reiner side two was just mindblowing. Unfortunately, the side one it was mated to was quite poor, and so, for now, it sets on a shelf waiting for a mate.

Ansermet’s performance with the Suisse Romande here may not have the uncanny precision of Reiner’s with the CSO, but he does manage to bring out most of the more lyrical elements that seem to hold less interest for Reiner.

The key element is the brass — it must have tremendous weight and power, otherwise the proceedings lose their energy. The copies without good weight to the brass, as well as richness in the lower strings fared poorly in our shootout.

Lessons Learned, 2015

There is a single stamper for each side that sounded better than any other. If you buy this record you will have the opportunity to learn what it is. It doesn’t always sound great, but when it does sound great, its greatness is unmistakable and simply cannot be denied.

There are certain stampers that seem to have a consistently brighter-than-it-should-be top end. They are tolerable some of the time, but the real magic can only be found on the copies that have a correct or even slightly duller top. Live classical music is never “bright” the way recordings of it so often are. (It’s rarely “rich” and “romantic” the way many vintage recordings are — even those we rave about — but that’s another story for another day.)

Vinyl Condition

Mint Minus Minus and maybe a bit better is about as quiet as any vintage pressing will play, and since only the right vintage pressings have any hope of sounding good on this album, that will most often be the playing condition of the copies we sell. (The copies that are even a bit noisier get listed on the site are seriously reduced prices or traded back in to the local record stores we shop at.)

Those of you looking for quiet vinyl will have to settle for the sound of other pressings and Heavy Vinyl reissues, purchased elsewhere of course as we have no interest in selling records that don’t have the vintage analog magic of these wonderful recordings.

If you want to make the trade-off between bad sound and quiet surfaces with whatever Heavy Vinyl pressing might be available, well, that’s certainly your prerogative, but we can’t imagine losing what’s good about this music — the size, the energy, the presence, the clarity, the weight — just to hear it with less background noise.

Side One

- The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship

- The Story of the Kalendar Prince

- The Young Prince And The Young Princess

Side Two

- Festival At Baghdad – The Sea

- Polovtsian Dances – Prince Igor: Borodin

Wikipedia on Scheherazade

Scheherazade, also commonly Sheherazade, Op. 35, is a symphonic suite composed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1888 and based on One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights).

This orchestral work combines two features typical of Russian music in general and of Rimsky-Korsakov in particular: dazzling, colorful orchestration and an interest in the East, which figured greatly in the history of Imperial Russia, as well as orientalism in general. The name “Scheherazade” refers to the main character Scheherazade of the One Thousand and One Nights. It is one of Rimsky-Korsakov’s most popular works.

During the winter of 1887, as he worked to complete Alexander Borodin’s unfinished opera Prince Igor, Rimsky-Korsakov decided to compose an orchestral piece based on pictures from One Thousand and One Nights as well as separate and unconnected episodes. After formulating musical sketches of his proposed work, he moved with his family to the Glinki-Mavriny dacha, in Nyezhgovitsy along the Cherementets Lake (near present-day Luga, in Leningrad Oblast). The dacha where he stayed was destroyed by the Germans during World War II.

During the summer, he finished Scheherazade and the Russian Easter Festival Overture. Notes in his autograph orchestral score show that the former was completed between June 4 and August 7, 1888. Scheherazade consisted of a symphonic suite of four related movements that form a unified theme. It was written to produce a sensation of fantasy narratives from the Orient.

Initially, Rimsky-Korsakov intended to name the respective movements in Scheherazade “Prelude, Ballade, Adagio and Finale.” However, after weighing the opinions of Anatoly Lyadov and others, as well as his own aversion to a too-definitive program, he settled upon thematic headings, based upon the tales from The Arabian Nights.

The composer deliberately made the titles vague so that they are not associated with specific tales or voyages of Sinbad. However, in the epigraph to the finale, he does make reference to the adventure of Prince Ajib. In a later edition, Rimsky-Korsakov did away with titles altogether, desiring instead that the listener should hear his work only as an Oriental-themed symphonic music that evokes a sense of the fairy-tale adventure, stating:

“All I desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond a doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements.”

He went on to say that he kept the name Scheherazade because it brought to everyone’s mind the fairy-tale wonders of Arabian Nights and the East in general.

Musical Overview

Rimsky-Korsakov wrote a brief introduction that he intended for use with the score as well as the program for the premiere:

“The Sultan Schariar, convinced that all women are false and faithless, vowed to put to death each of his wives after the first nuptial night. But the Sultana Scheherazade saved her life by entertaining her lord with fascinating tales, told seriatim, for a thousand and one nights. The Sultan, consumed with curiosity, postponed from day to day the execution of his wife, and finally repudiated his bloody vow entirely.”

The grim bass motif that opens the first movement represents the domineering Sultan.

This theme emphasizes four notes of a descending whole tone scale: E–D–C–B♭ (each note is a down beat, i.e. first note in each measure, with A♯ for B♭). After a few chords in the woodwinds, reminiscent of the opening of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream overture, the audience hears the leitmotif that represents the character of the storyteller herself, Scheherazade. This theme is a tender, sensuous, winding melody for violin solo, accompanied by harp.

Rimsky-Korsakov stated:

“The unison phrase, as though depicting Scheherazade’s stern spouse, at the beginning of the suite appears as a datum, in the Kalendar’s Narrative, where there cannot, however, be any mention of Sultan Shakhriar. In this manner, developing quite freely the musical data taken as a basis of composition, I had to view the creation of an orchestral suite in four movements, closely knit by the community of its themes and motives, yet presenting, as it were, a kaleidoscope of fairy-tale images and designs of Oriental character.”

Rimsky-Korsakov had a tendency to juxtapose keys a major third apart, which can be seen in the strong relationship between E and C major in the first movement. This, along with his distinctive orchestration of melodies which are easily comprehensible, assembled rhythms, and talent for soloistic writing, allowed for such a piece as Scheherazade to be written.

The movements are unified by the short introductions in the first, second and fourth movements, as well as an intermezzo in the third. The last is a violin solo representing Scheherazade, and a similar artistic theme is represented in the conclusion of the fourth movement. Writers have suggested that Rimsky-Korsakov’s earlier career as a naval officer may have been responsible for beginning and ending the suite with themes of the sea. The peaceful coda at the end of the final movement is representative of Scheherazade finally winning over the heart of the Sultan, allowing her to at last gain a peaceful night’s sleep.

The music premiered in Saint Petersburg on October 28, 1888, conducted by Rimsky-Korsakov.

The reasons for its popularity are clear enough; it is a score replete with beguiling orchestral colors, fresh and piquant melodies, a mild oriental flavor, a rhythmic vitality largely absent from many major orchestral works of the later 19th century, and a directness of expression unhampered by quasi-symphonic complexities of texture and structure.

Movements

The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship

This movement is made up of various melodies and contains a general A B C A′ B C′ form. Although each section is highly distinctive, aspects of melodic figures carry through and unite them into a movement. Although similar in form to the classical symphony, the movement is more similar to the variety of motives used in one of Rimsky-Korsakov’s previous works, Antar. Antar, however, used genuine Arabic melodies as opposed to Rimsky-Korsakov’s own ideas of an oriental flavor.

The Story of the Kalendar Prince

This movement follows a type of ternary theme and variation and is described as a fantastic narrative. The variations only change by virtue of the accompaniment, highlighting the piece’s “Rimsky-ness” in the sense of simple musical lines allowing for greater appreciation of the orchestral clarity and brightness. Inside the general melodic line, a fast section highlights changes of tonality and structure.

The Young Prince and the Young Princess

This movement is also ternary and is considered the simplest movement in form and melodic content. The inner section is said to be based on the theme from Tamara, while the outer sections have song-like melodic content. The outer themes are related to the inner by tempo and common motif, and the whole movement is finished by a quick coda return to the inner motif, balancing it out nicely.

Festival at Baghdad. The Sea. The Ship Breaks against a Cliff Surmounted by a Bronze Horseman

This movement ties in aspects of all the preceding movements as well as adding some new ideas, including an introduction of both the beginning of the movement and the Vivace section based on Sultan Shakhriar’s theme, a repeat of the main Scheherazade violin theme, and a reiteration of the fanfare motif to portray the ship wreck. Coherence is maintained by the ordered repetition of melodies, and continues the impression of a symphonic suite, rather than separate movements. A final conflicting relationship of the subdominant minor Schahriar theme to the tonic major cadence of the Scheherazade theme resolves in a fantastic, lyrical, and finally peaceful conclusion.